Douleur et Rébellion

Elisabeth investigates the relevance of political cinema for the development of her choreographic and scenic work. She draws on her personal history and observations of class and society.

Film creates an alternate perception of time, with involuntary flashbacks and synchronous experience of different time dimensions. It’s a dream, a floating visual language that unfolds. This language taps into the subconscious, reorganizes it, and connects directly to our deepest, buried patterns. That creates the potential of a direct impact on the spectator, and therefore of change. Elisabeth wants to expose the interaction/exchange between spectator and political reality, and depict it through scenic and choreographic means.

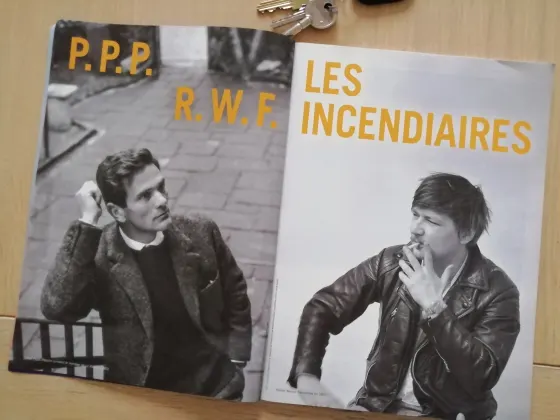

She chose 3 filmmakers—Fassbinder, Pasolini and Schroeter—to examine which models and strategies they offer for making a political dance. She thus balances on the intersection of politics, film theory and choreography, hoping to find a dance with a direct and real impact.

The key questions are: How can choreography generate political awareness and impact? How do you make political dance or do you make dance political? How do you talk about fascism and ideology in these times of political radicalization and hardening? Do these filmmakers fit into a tradition of queerness, and is that relevant in the contemporary identity discourse? What role do the senses, the nervous system, and 'affect' have in the development of political beliefs? And: how does all of this relate to making aesthetic and scenic choices?

Douleur et Rébellion is currently supported by DansBrabant, Performance Technology Lab, Wpzimmer, Walpurgis, Cultuurhuis de Warande and is receiving financial support from DeBuren/Grensverleggers.

As part of her research for this work, Elisabeth participated in Lab #12, an initiave by the Performance Technology Lab.

Fassbinder’s subjects are the bankruptcy of the bourgeois morality, the free market for humanistic ideals, the double standards of the new meritocracy, and the ubiquitous black market for sex, love and other addictions that are driving our performance-driven lives.

With Fassbinder, everyone tries to sell their skin more dearly, or squander their love to the highest bidder, and in the end they all come out disappointed. Traveling salespeople, dealers, pimps and other middlemen are the wretched heroes of this world. But their stories are more than only the distorted self-image of disappointed idealism with which the first post-war generation of Germans took it out, expressing their distaste for the materialistic society and their aversion to mediocrity, inspired or not from ascetic or orgiastic motives.

Fassbinder’s heroes are too rebellious for such “left-wing melancholy” and too much realist in their survival strategy and—in some cases—also too utopian. They behave as if, thanks to this trade and barter on the black markets of heart and soul, new opportunities will still arise; as if their share price will still be quoted and new energy will be released that will turn human relations for the better.